the last question

A Camel is a Horse Designed by Committee

Jan 5, 2025

Have all the jobs been fake for years? Read this, a NASA critique from 1992.

Basically society is run by useless people making work for other useless people so that together they can all alleviate their deep concern about not having a place in society.

— George Hotz (@realGeorgeHotz) Nov 20, 2024

guy creating immense value as a cog in a wonderful machine built by an alien superintelligence immanent on earth: pretty sure I have a fake job

— roon (@tszzl) July 2, 2025

NOTE: The following talk was delivered in a conference room; the prelude is included here as spoken for context.

I want to begin with an apology of sorts. It feels strange to be standing here saying goodbye when I didn’t really get to know many of you deeply. I’m not the most social person by nature. More than that, I’ve been dealing with a disc hernia for most of my time here, which kept me more withdrawn than I would’ve liked, both physically and in spirit, I’ve missed out on getting to know many of you better.

So if this farewell feels solitary or impersonal, that is entirely on me, and I’m sorry for it. Please forgive the awkwardness of it all.

The work we do here matters, but the people we do it with matter more. I should have tried harder to be part of that.

Before I share what I’ve learned, I want to say this: everything I’m about to share comes from hope. Hope that this sparks meaningful conversations about how we work.

I’ve had the privilege of working with remarkable minds here, and what follows isn’t an indictment, it’s an observation. What follows might sound critical of processes and systems we all work within, but I’m not here to teach or suggest anyone is doing anything wrong. Far from it.

These are simply observations from someone who’s been thinking about why certain patterns emerge in organizations, and why smart people with good intentions might sometimes struggle to build the things they set out to build.

Institutions, like all complex systems, often evolve for stability. But I believe progress demands something else: error correction, and the courage to create explanations, not just procedures. I’ve learned a lot here: about creativity, about collaboration, about the gap between what we intend and what we achieve. Some of these lessons have been uncomfortable, but all of them have been valuable.

Parts of this narrative might seem to oversimplify complex organizational dynamics, may contain errors of judgement, or be simply wrong. This is inevitable. But that’s exactly why we need error correction. What is good and evil can be sometimes ambiguous, context-dependent. But you can be certain that whatever hinders error correction is evil.

So take this as an invitation: to build systems that actively seek truth, not just avoid failure.

Today I want to tell you three stories. That’s it. No big deal. Just three stories.

One story is about the past, one story is about the present and one is about the future.

The first story is about mistaking motion for progress.

Past

During World War II, on remote islands in the South Pacific, indigenous tribes witnessed something surreal: giant metal birds landing from the sky, bringing food, tools, clothing, riches beyond imagination. These “cargo” drops were meant for stationed soldiers, but the islanders saw only the ritual: airstrips carved from jungle, men waving signals, wooden towers with antennas.

After the war, the planes stopped. But the islanders remembered. So they built their own runways out of dirt. They crafted headphones from coconuts. They waved sticks in the air, hoping to summon the planes again.

To truly understand, the islanders would have needed to grasp what a warplane was, what a war was, what global conflict meant. What was a plane doing in a war? Why planes landed where they did. What was the purpose of an airport, a runway, a tower, a signal? And hence why their efforts were of no use.

They weren’t stupid. They were imitating the visible behaviors of success, without understanding the invisible systems underneath. There is a name for this phenomenon: cargo cult. [0]

Everyone says they want to be a “great team.” But what does that really mean? I’m not sure I know. Most people never ask. No one defines it. We just default to more meetings, more process, more “alignment” initiatives. Is this just cargo cult management? It feels productive, but is it? Sometimes I wonder if it’s motion, not progress.

The real blockers aren’t always what we complain about in Monday standups. Sometimes it’s the stuff we have stopped seeing. The assumptions baked so deep into the culture we forgot they were assumptions. I catch myself optimising for optics, navigating unnecessarily hierarchical team structures, shipping presentations instead of shipping product.

That’s not design. That’s performance theater. Or maybe it’s just what happens in large groups.

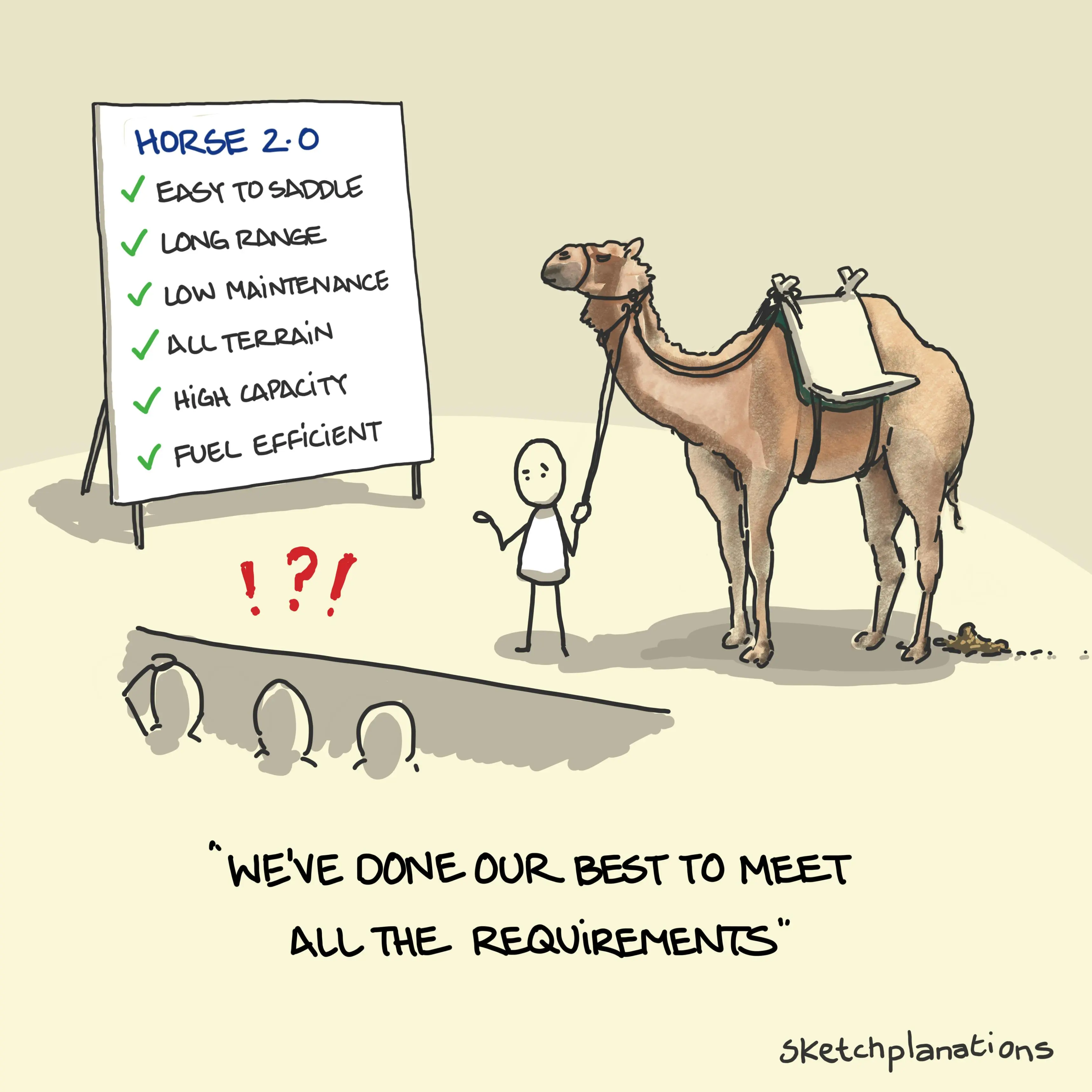

The second story is about horses and camels.

Present

When I was 14, I touched Photoshop for the first time. It felt like magic. Here was this tool that could turn an idea in my head into reality on screen. Just pure creative possibility at my fingertips.

Years later, I found myself at Adobe. When I joined Express, I thought I’d be helping create that kind of magic. The pitch was compelling: help build tools that would unlock creativity for millions. That’s the sort of goal that makes you eager to open your laptop in the morning. Instead, I discovered something else: a machine that turns good ideas into meetings.

The problem, I’ve realized, is that we might be optimizing for the wrong things.

Process

There’s a kind of mental bait and switch that happens at big companies. They show you the amazing things they’ve built. But what they don’t tell you is that those things were probably built before the processes that would prevent them from being built today.

The core problem is one I’ve seen before: as companies scale, they try to prevent bad things from happening by adding processes. But processes are like organizational scar tissue. They protect you from past injuries while gradually restricting your movement.

The thing about large orgs is that they’re optimized for not failing rather than for succeeding. This sounds like the same thing, but it isn’t. Not failing means adding processes, checkpoints, and “alignment.” Succeeding means taking risks and moving fast. [1]

This is what optimizing for not failing looks like in practice: You have an idea for a feature that would help users. Simple thing. Should take a week to prototype. But first, you need to “align with stakeholders.” Team A needs to review it. Team A thinks Team B should weigh in. Team B wants Team C’s perspective. Team C suggests forming a working group. Three months later, your week-long project has turned into a “strategic initiative” with its own Slack channel and weekly syncs.

This happens so gradually that most people don’t notice it. The tragedy isn’t that anyone is deliberately trying to prevent good work - it’s that the system has evolved to prevent it. It’s like a game of whispers, except instead of a message getting garbled, an idea gets diluted. [2]

Camels

The fascinating thing is that nothing obviously wrong is happening. Everyone involved is smart. They’re trying to be thorough. But the system has evolved to optimize for consensus rather than quality.

This isn’t unique to Adobe. As organizations grow, they naturally accumulate processes to manage complexity. The problem is when these processes become more important than the outcome itself. It’s like the story of the committee that was formed to design a horse and ended up creating a camel. [3]

The management situation also illustrates this dynamic. My direct manager is highly competent. But the incentive structure rewards for predictability over breakthroughs. When you optimize for predictability, you get exactly what you’d expect: predictable results.

This is a systems problem, not a people problem. Young companies don’t have this problem because they can’t afford to. They have to focus on building things users want. But as companies get bigger, they start to focus on not making mistakes. The result is that they make the biggest mistake of all: they stop making anything remarkable. [4]

The third story is about choosing to build the plane rather than wave the sticks.

Future

Leaving a job is rarely simple. For me, the hardest part isn’t the act itself, but explaining why I’m leaving without sounding ungrateful or bitter. I want to be honest, and I hope that honesty is useful.

I should mention that Adobe is a remarkable company. A company that has fundamentally changed how humans create. Working here has been a privilege. I’ve learned a lot about what helps people do their best work, and what can get in the way. Sometimes, the most valuable thing you learn from an experience is what you want to seek out next, and what you’d rather avoid.

I’m leaving because I want to be in a place where ideas can grow quickly, without getting tangled in too much process. I’ve noticed that the people I admire most are always trying to do more with what they learn. That’s what I am doing now.

The standard advice about leaving jobs is to avoid burning bridges. But I think we need a different standard: the best way to be fair to an organization is to be honest about why you’re leaving. Not to criticize, but to help others learn from your experience.

This is what I learned: the environment you work in shapes what you can achieve. That might sound obvious, but it’s easy to forget. You can’t make something extraordinary in a place that’s designed to avoid mistakes at all costs, any more than a group of people can write a poem, each person reaching for the pen after every word, debating and revising every line as it’s written.

To the amazing people I worked with at Adobe: thank you. You’ve taught me more than you know. To those thinking about similar transitions: optimize ruthlessly for learning rate and impact. Everything else is secondary.

Looking ahead, I’m optimistic. The future of creative tools is wide open. AI is fundamentally changing how we interact with computers. The world needs tools that genuinely amplify human creativity, not just that are good enough to justify a subscription fee.

This might come off as critical. It’s not meant to be. Adobe is a strong company with exceptional people. These problems aren’t unique to Adobe, and they aren’t permanent. The good news is that these problems are fixable. The bad news is that fixing them would require fundamental changes to how the organization works. And large orgs, like large ships, change direction slowly.

I hope Adobe finds a way to move fast enough to lead that future. But I can’t wait around to find out.

Life seems too short to spend in meetings about meetings.[5]

Notes

[0] Richard Feynman famously used the phrase”cargo cult science” to describe research that looks scientific but lacks scientific rigor. ↩︎

[1] “Stakeholder alignment” is often corporate speak for diluting ideas until they’re acceptable to everyone – and thus exciting to no one. ↩︎

[2] This mirrors Conway’s Law: organizations design systems that mirror their communication structure. When your organization is optimized for meetings and consensus, your products inevitably reflect that. ↩︎

[3] This saying is believed to originate from a French political maxim: “A camel is a horse designed by committee” (“Un chameau est un cheval dessiné par un comité”). It captures something important: when too many people try to design something, you get exactly what you’d expect - a creature that looks like it was built from spare parts. The French came up with this in the 1950s, probably after sitting through too many meetings themselves. ↩︎

[4] Adobe’s historical successes came from small teams moving quickly. Photoshop was originally created by Thomas and John Knoll working as a duo. After Adobe acquired it, they kept the team deliberately small for years. Similar story with Illustrator. ↩︎

[5] The most dangerous aspect of such a culture is how it trains people to seek permission rather than forgiveness. This fundamentally changes how people approach problems: instead of asking “How can I solve this?” they ask “Who do I need to convince to let me try?” ↩︎