the last question

How to Land on the Moon

June 30, 2025

I wanted to land the thing.

The first sincere attempt was lander2.py. It could sometimes avoid immediate crash, which felt like progress. But it wasn’t landing.

Reinforcement learning is dumb. Unlike supervised learning where your errors are independent, in RL, your model makes an error, and that error changes the next state you see. The errors compound. The lander would learn a perfect, stable hover, draining fuel until the episode timed out. It was gaming the reward system, getting a decent score for simply not crashing. But it wasn’t landing.

I did make it land, eventually. Here’s the code.

This is how you do it

First, we define the environment. The rewards are sparse, so we run multiple environments in parallel. More examples, more diversity, faster convergence.

env_name = 'LunarLanderContinuous-v3'

state_dim = 8

action_dim = 2

num_envs = int(os.getenv('NUM_ENVS', 8))

Define the network. The actor outputs actions, and the critic estimates state values. The tanh keeps the actions in the range [-1, 1]. The critic learns the value function. A value function is a scalar that estimates the cumulative expected discounted return for a state.

class ActorCritic(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, state_dim, action_dim, hidden_dim, num_hidden_layers):

super(ActorCritic, self).__init__()

self.actor_layers = nn.ModuleList()

self.critic_layers = nn.ModuleList()

if num_hidden_layers < 1: raise ValueError("num_hidden_layers must be at least 1")

# Actor network

self.actor_layers.append(nn.Linear(state_dim, hidden_dim))

for _ in range(num_hidden_layers - 1): self.actor_layers.append(nn.Linear(hidden_dim, hidden_dim))

self.actor_out = nn.Linear(hidden_dim, action_dim)

# Critic network

self.critic_layers.append(nn.Linear(state_dim, hidden_dim))

for _ in range(num_hidden_layers - 1): self.critic_layers.append(nn.Linear(hidden_dim, hidden_dim))

self.critic_out = nn.Linear(hidden_dim, 1)

def forward(self, state):

x = state

for layer in self.actor_layers: x = F.relu(layer(x))

action_mean = torch.tanh(self.actor_out(x))

v = state

for layer in self.critic_layers: v = F.relu(layer(v))

value = self.critic_out(v)

return action_mean, value

Store rollout data in lists.

class Memory:

def __init__(self):

self.states = []

self.actions = []

self.logprobs = []

self.rewards = []

self.is_terminals = []

Define the PPO policy. Mathematically, a policy is a mapping from states to actions. In RL, the policy is a function that takes a state and outputs an action. Here, the policy is parameterized by a neural network. Note that the actor and critic are optimized separately.

class PPO:

def __init__(self, actor_critic, lr_actor, lr_critic, gamma, lamda, K_epochs, eps_clip, action_std, batch_size):

self.actor_critic = actor_critic

# Use separate optimizers for actor and critic to decouple updates

actor_params = [p for n, p in actor_critic.named_parameters() if 'actor_' in n]

critic_params = [p for n, p in actor_critic.named_parameters() if 'critic_' in n]

self.actor_optimizer = optim.Adam(actor_params, lr=lr_actor)

self.critic_optimizer = optim.Adam(critic_params, lr=lr_critic)

self.gamma = gamma

self.lamda = lamda

self.K_epochs = K_epochs

self.eps_clip = eps_clip

self.action_std = action_std

self.batch_size = batch_size

Why PPO

There are a bunch of RL algorithms to choose from. OpenAI’s Spinning Up lists the main ones:

- Vanilla Policy Gradient (VPG): Basic policy gradients from the 80s/90s

- Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO): Stable but annoying to implement

- Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO): TRPO without the headache

- Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG): Off-policy, fast but unstable

- Twin Delayed DDPG (TD3): DDPG with fixes

- Soft Actor-Critic (SAC): Good sample efficiency, entropy regularization

Karpathy’s Pong from Pixels explains why policy gradients are appealing: they directly optimize expected reward. But there’s a catch. Policy gradients are slow because you’re essentially doing gradient ascent on a noisy function. Each episode gives you one sample of the return, and that sample has high variance. You need thousands of episodes to get a decent gradient estimate. This is why RL takes forever compared to supervised learning where you have clean labels.

Schulman et al. solved the stability problem of policy gradients with a clever trick: clip the objective function.

The PPO loss is defined like this:

\[L^{CLIP}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_t \left[ \min \left( r_t(\theta) \hat{A}_t, \text{clip}(r_t(\theta), 1-\varepsilon, 1+\varepsilon) \hat{A}_t \right) \right]\]Where \(r_t(\theta)\) is the probability ratio:

\[r_t(\theta) = \frac{\pi_\theta(a_t \mid s_t)}{\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(a_t \mid s_t)}\]and \(\hat{A}_t\) is the advantage.

When the ratio gets too big (policy changed too much), the gradient gets clipped. This prevents catastrophic policy updates that would ruin your training. It’s way simpler than TRPO’s trust region math but gives you similar stability. A fancy way of saying “don’t change the policy too much”.

Compute the actor and critic losses. The critic loss is simple mean squared error between predicted and target values.

def compute_losses(self, batch_states, batch_actions, batch_logprobs, batch_advantages, batch_returns):

action_means, state_values = self.actor_critic(batch_states)

std_tensor = torch.ones_like(action_means) * self.action_std

dist = torch.distributions.Normal(action_means, std_tensor)

action_logprobs = dist.log_prob(batch_actions).sum(-1)

state_values = torch.squeeze(state_values)

# PPO actor loss with clipping

ratios = torch.exp(action_logprobs - batch_logprobs.detach())

surr1 = ratios * batch_advantages

surr2 = torch.clamp(ratios, 1 - self.eps_clip, 1 + self.eps_clip) * batch_advantages

actor_loss = -torch.min(surr1, surr2).mean()

# Critic loss

critic_loss = F.mse_loss(state_values, batch_returns)

return actor_loss, critic_loss

Compute advantages using Generalized Advantage Estimation (GAE). GAE balances bias and variance, improving the stability of policy updates.

def compute_advantages(self, rewards, state_values, is_terminals):

T, N = rewards.shape

device = rewards.device

returns = torch.zeros_like(rewards)

state_values_pad = torch.cat([state_values, state_values[-1:]], dim=0)

gae = torch.zeros(N, device=device)

for t in reversed(range(T)):

delta = rewards[t] + self.gamma * state_values_pad[t + 1] * (1 - is_terminals[t]) - state_values_pad[t]

gae = delta + self.gamma * self.lamda * (1 - is_terminals[t]) * gae

returns[t] = gae + state_values_pad[t]

advantages = returns - state_values_pad[:-1]

return advantages.reshape(-1), returns.reshape(-1)

But What is GAE?

Schulman et al. (same guy, different paper) solved another problem. Policy gradients have high variance. You can reduce variance by using a value function to estimate future rewards instead of waiting for actual returns. But then you introduce bias. Classic bias-variance tradeoff.

Instead of picking one way to estimate advantages, combine them all. You can estimate advantages using 1-step returns, 2-step returns, or full episode returns. GAE weights them exponentially:

\[\hat{A}_t^{GAE(\gamma,\lambda)} = \sum_{l=0}^{\infty} (\gamma \lambda)^l \delta_{t+l}^V\]Where \(\delta_t^V = r_t + \gamma V(s_{t+1}) - V(s_t)\) is the temporal difference error.

When \(\lambda = 0\), you get pure 1-step estimation (high bias, low variance). When \(\lambda = 1\), you get full episode returns (low bias, high variance). Values in between let you tune the tradeoff.

Short-term estimates are more accurate but biased. Long-term estimates are unbiased but noisy. GAE lets you blend them smoothly. In practice, \(\lambda = 0.95\) works well for most tasks.

Actions are sampled from a Gaussian distribution centered around the actor’s predicted mean. This encourages exploration during training.

def select_action(self, state, memory):

state_tensor = torch.as_tensor(state, dtype=torch.float32)

with torch.no_grad():

action_mean, _ = self.actor_critic(state_tensor)

std_tensor = torch.ones_like(action_mean) * self.action_std

dist = torch.distributions.Normal(action_mean, std_tensor)

action = dist.sample()

action_logprob = dist.log_prob(action).sum(-1)

return action.detach().cpu().numpy()

The main training loop collects rollouts and triggers updates periodically.

def train(env_name, max_episodes, max_timesteps, update_timestep, log_interval, state_dim, action_dim, hidden_dim, lr_actor, lr_critic, gamma, K_epochs, eps_clip, action_std, gae_lambda, batch_size, num_envs=1):

while completed_episodes < max_episodes:

actions = ppo.select_action(states, memory)

next_states, rewards, terminated, truncated, _ = env.step(actions)

memory.rewards.append(rewards)

# the rest of the lines give you speed (parallelism), logging, and plotting

if timestep % update_timestep == 0:

ppo.update(memory)

memory.clear_memory()

states = next_states

The update function uses mini-batches and multiple epochs to squeeze knowledge from each rollout. Note that the actor and critic are updated separately because they have different learning rates.

def update(self, memory):

with torch.no_grad():

# Convert memory to tensors and compute advantages

rewards = torch.as_tensor(np.stack(memory.rewards), dtype=torch.float32)

# rest of tensor conversion lines...

advantages, returns = self.compute_advantages(rewards, old_state_values_reshaped, is_terms)

dataset = TensorDataset(old_states, old_actions, old_logprobs, advantages, returns)

dataloader = DataLoader(dataset, batch_size=self.batch_size, shuffle=True)

for _ in range(self.K_epochs):

for batch in dataloader:

# rest of batch processing lines...

actor_loss, critic_loss = self.compute_losses(

batch_states, batch_actions, batch_logprobs, batch_advantages, batch_returns

)

# Update actor

self.actor_optimizer.zero_grad()

actor_loss.backward(retain_graph=True)

torch.nn.utils.clip_grad_norm_(

[p for n, p in self.actor_critic.named_parameters() if 'actor_' in n],

max_norm=0.5

)

self.actor_optimizer.step()

# Update critic

self.critic_optimizer.zero_grad()

critic_loss.backward()

torch.nn.utils.clip_grad_norm_(

[p for n, p in self.actor_critic.named_parameters() if 'critic_' in n],

max_norm=1.0

)

self.critic_optimizer.step()

Evaluate the policy without exploration noise using deterministic actions.

def evaluate_policy(env_name, actor_critic, max_timesteps, num_envs=16):

env = gym.vector.SyncVectorEnv([lambda: gym.make(env_name) for _ in range(num_envs)])

states, _ = env.reset()

total_rewards = np.zeros(num_envs, dtype=np.float32)

with torch.no_grad():

for _ in range(max_timesteps):

action_mean, _ = actor_critic(torch.as_tensor(states, dtype=torch.float32))

actions_np = action_mean.cpu().numpy() # No sampling, deterministic

states, rewards, terminated, truncated, _ = env.step(actions_np)

total_rewards += rewards

return float(total_rewards.mean())

Once solved, render the policy for human observation.

def render_policy(env_name, actor_critic, max_timesteps):

env = gym.make(env_name, render_mode='human')

state, _ = env.reset()

with torch.no_grad():

for _ in range(max_timesteps):

action_mean, _ = actor_critic(torch.as_tensor(state, dtype=torch.float32).unsqueeze(0))

action = action_mean.squeeze(0).cpu().numpy()

state, reward, done, trunc, _ = env.step(action)

if done or trunc:

break

Training stops when evaluation consistently hits the target score (200 is fine, but arguably stricter 240 gives you a better policy).

The solution is beautiful_lander.py, a basic PPO implementation with every screw tightened. What do we learn?

-

One environment is too slow. You need an multiple landers learning in parallel. More data, more diversity, less time.

- Stability is everything. PPO is notoriously unstable. You have to chain it down.

- Orthogonal initialization so the network doesn’t explode on the first pass.

- Gradient clipping so the updates aren’t insane.

- Value function clipping so the critic doesn’t get too far ahead of itself.

- (Optional) An entropy bonus that decays over time. This forces it to explore early and exploit later.

- (Optional) An adaptive learning rate that slows down if the policy starts thrashing.

-

The actor’s learning rate (2e-4) is slower than the critic’s (8e-4), because we let the critic lead.

- (Optional) Punish cheating. No more gaming the system. The hovering lander was a problem. Maybe a penalty of -100 for not landing. Or a penalty gradient depending on the distance from the landing pad.

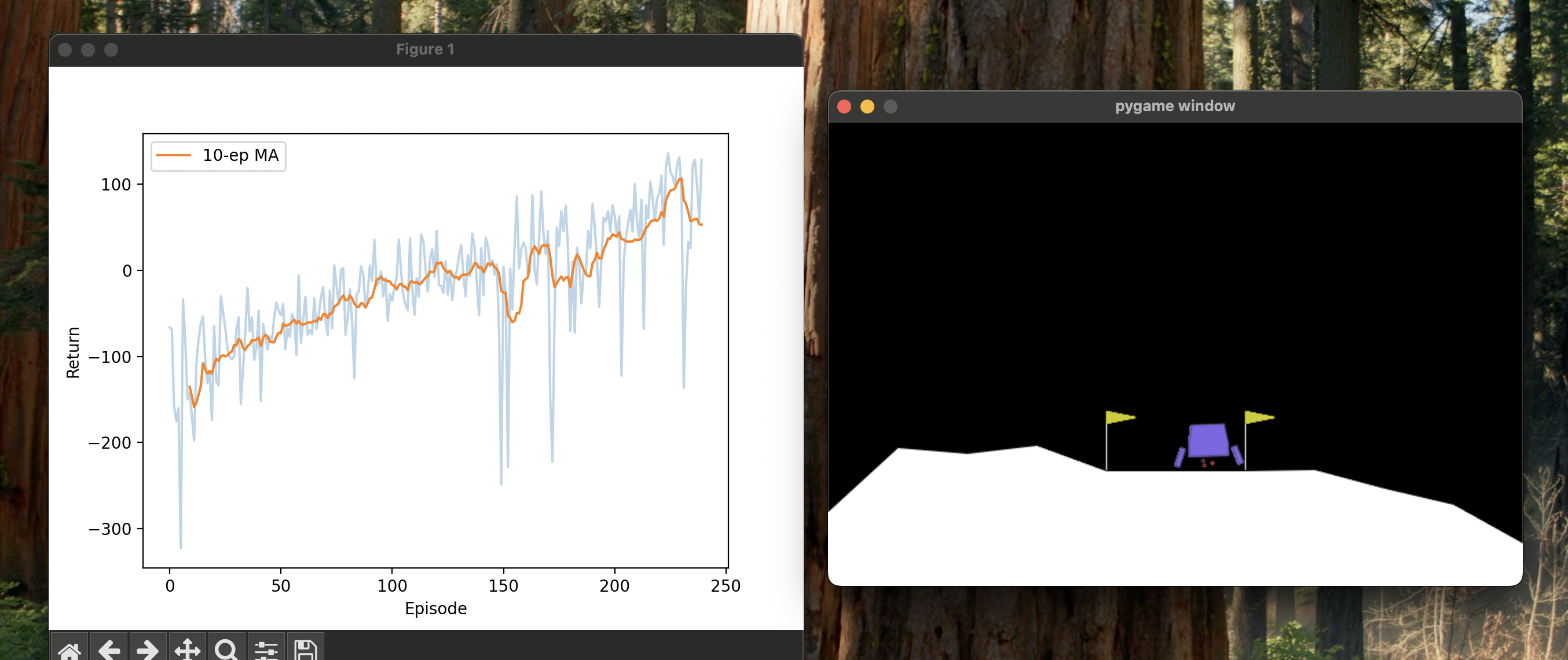

It’s a pile of hacks. But it works. It lands on the moon. Beautifully. Within 500 episodes, reliably.

One small step for a policy, one giant leap for my GPU bill.